Stop Asking Me About Inspiration

Navigating art, autism, and dialogue — the questions I’d prefer people to ask

(*This essay is part of my larger project, Art on the Spectrum, an illustrated memoir about autism, art, and the search for connection.*)

Opening: Setting the Stage

Almost every time I show my work, the question arises: “What inspires you?”

It is among the most common questions posed to artists, and yet, for me, it has always been the most unsatisfying. (See also: Artspace: 5 Questions Artists Hate)

I want to be clear: I deeply value when people engage me about my work. It takes courage to approach an artist at all. For many visitors, the gallery is an unfamiliar and even intimidating space, where the fear of “saying the wrong thing” can make silence seem safer.

I understand that feeling. I don’t have a formal art degree, and I certainly haven’t mastered the vast history of art. Surrounded by people who know every movement and painter, I sometimes feel intimidated myself.

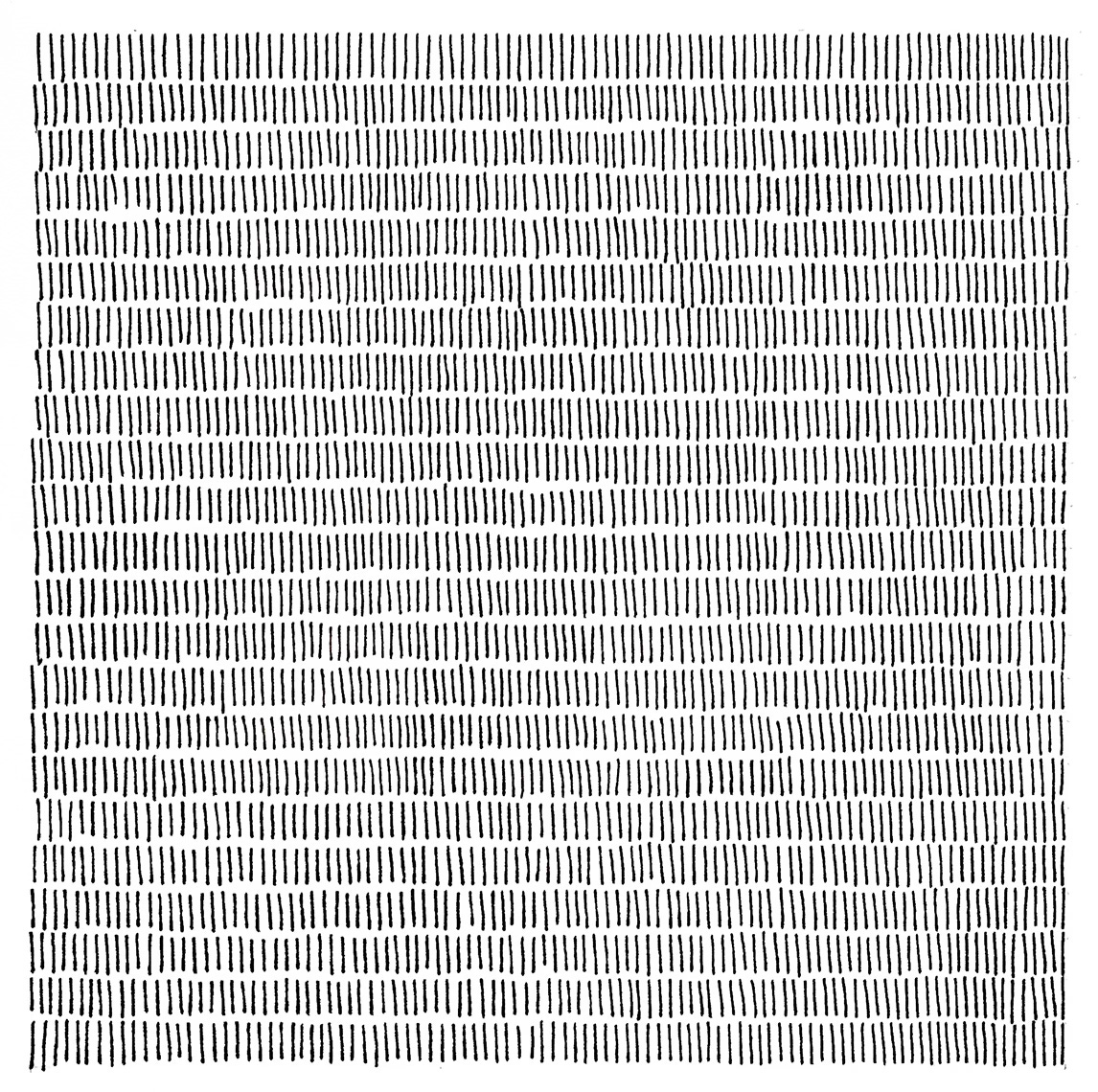

What I know is what I do: I put pen to paper and create. That is my art.

And let’s be honest — there are people who like to show off what they know. They use knowledge as a kind of gatekeeping, and it can make others feel small. I’ve always been turned off by that.

In education, there’s an old phrase that captures the difference: the “sage on the stage” versus the “guide on the side.” A sage on the stage often treats knowledge like a dump truck — they back it up, unload it into what they imagine are empty minds, and expect students to absorb, memorize, and spit it back.

That is not pedagogically sound education.

A guide on the side works differently. They meet people where they are, invite them to engage, and lead them toward deeper understanding. That, to me, is the spirit in which art should be shared.

Patterns repeat. So do questions.

The Problem with the Inspiration Question

So why does this one question — “What inspires you?” — feel so unsatisfying?

Part of it is that it assumes art begins with a lightning bolt or some sudden “revelation,” to use religious-like language. As if I sit around waiting for a muse to whisper in my ear, and only then do I pick up the pen. Perhaps, some artists do that, but I haven’t met one yet.

That’s not my reality. My process is rhythm and practice — showing up, again and again, until the work takes shape. Consistency matters — maybe someday I will even be more consistent in posting my work to social media!

Another problem with the inspiration question is that it flattens the complexity of art into one neat answer.

People might then expect me to name a person, a movement, or an emotion

(See also: IndianArtIdeas: 11 Annoying Questions).

But for me, and for many artists I know, there isn’t a single “source” of inspiration. There’s just the practice of doing, or the process. In fact an art professor friend said years ago that it was all about the process, not the end result.

Of course, some artists do talk about inspiration, and I don’t mean to suggest that everyone feels the same way I do.

But even then, the word is slippery. Maybe it’s less about “inspiration” and more about what an artist was thinking about as they drew the way they did.

And even that is hard to pin down.

For example, I often listen to music while I work. Sometimes a particular song comes on and suddenly I see the drawing in a new way. But the truth is, it could have been any number of songs. That one happened to tilt my perception in a certain direction, but another might have done something entirely different.

The process is fluid, not fixed.

Even after a piece is finished, my sense of it can shift. Once it’s out in the world, people bring their own perspectives, and I see it differently again through their eyes. The meaning is never static.

That’s why the inspiration question often feels like a dead end. It asks for something final, when in reality the process is always in motion.

That’s why the inspiration question often feels like a dead end. It asks for something final, when in reality the process is always in motion.

Questions Artists Dislike

The inspiration question is just the beginning. Most artists I know could rattle off a whole list of questions that make us cringe (See also: HelloArtsy: 8 Comments Artists Hate).

Some are tired clichés, others are simply awkward, and a few are downright insulting.

Here are a few of the greatest hits:

- “What inspires you?” — cliché and overused.

- “What does this piece mean?” — as if every work has a single neat answer.

- “When did you first know you wanted to be an artist?” — the forced “origin story.”

- “Who is your favorite artist?” — reductive, forcing comparison.

- “How was your mood when you made this?” — assumes emotions map neatly onto output.

- “Did you draw that?” — insulting in its simplicity.

(See also: Medium: 7 Things You Need to Stop Saying to Artists).

- “I see clouds/faces/animals in this…” — as if the point of the work is for you to play Rorschach test with it.

- “This reminds me of [insert artist/thing].” — a comparison that shifts attention away from what’s in front of them.

I’ve lost count of how many times someone has pointed at my drawings and announced they saw a face, a bird, or a cloud. Honestly, it doesn’t mean much to me in that setting — it feels more like projection than conversation.

The same goes for casual comparisons: once in a while they might be insightful, but more often they’re generic, even mundane.

But within a small circle of trusted artist friends, these kinds of observations are different.

I regularly share work with two close friends — both left-handed, both professors at different points in their lives. We named ourselves the Left Hand Group (LHG). Before the pandemic we’d meet once a month for pizza and beer, and during COVID we shifted to weekly Zoom calls. Those meetings were a lifeline, keeping us connected and creative during an isolating time.

In that group, if someone says, “I see a face in this” or “This reminds me of X’s work,” it’s not small talk. It’s critique. It gives me the chance to decide: do I want to lean into that resemblance, or do I need to adjust the work so it says something different?

That kind of feedback is invaluable.

But outside that trusted circle, when strangers make the same comment at a show, it rarely goes anywhere. That’s the difference: in the right context, specific observations are a gift. In the wrong one, they shut down dialogue instead of opening it.

A Neurodivergent Lens

As an autistic (Aspie) artist, vague and generic questions can be especially frustrating

(See also: Create Me Free: Art Meets Autism/Neurodiversity). Neurodivergence often comes with a preference for specificity and clarity, and that shapes the way I respond to people engaging with my work.

But I don’t want this to sound like I’m scolding anyone or demanding that you read my mind. When you meet me at a show, you can’t possibly know what I want to be asked — and that’s okay. What I’m trying to do here is pull back the curtain a little, to explain why certain questions feel like dead ends, and why more specific ones open the door to real conversation.

This isn’t about alienating people; it’s about helping them understand.

And to be honest, going to an opening where my work is on display raises my anxiety like nothing else.

Today, in fact, I’m heading to my very first exhibition in California. You’d think I’d be thrilled — and in a way I am — but mostly I don’t even want to go. The idea of walking into that room makes me want to turn around.

I’ll be wondering where they placed my piece on the wall, I’ll want to study the other art, and I’ll know I should talk with other artists because this is the community I hope to integrate into.

But the truth is, I’d rather sneak in when nobody’s there, look around in silence, and slip back out.

Honestly, there are times when like today when I’d rather have no questions. Okay, that’s a bit extreme. That has more to do with discomfort in crowds or unfamiliar situations than it art, I suppose.

That’s the part of being autistic that most people don’t see. Social situations like this don’t just make me nervous; they make me want to retreat. Which is why, when someone does step forward to talk with me, it matters so much that the conversation feels genuine.

Specificity isn’t about rules — it’s about connection, and for me, that’s what makes these moments bearable, even meaningful.

Because of all these factors, I often prefer to attend my own shows with a companion. Having someone beside me takes away the pressure of standing alone, waiting for someone to approach, or feeling like I need to approach others. A companion provides a buffer, a sense of steadiness in a situation that otherwise feels overwhelming.

Neurodivergent vs. Neurotypical Preferences

I often wonder if neurodivergent artists dislike different questions than neurotypical artists.

In some ways, the answer is yes. In other ways, not really. Of course, I don’t want to simplify the diversity of ways in which neurodivegency manifests itself. There’s definitely overlap. Almost everyone rolls their eyes at clichés like “What inspires you?” or “Who’s your favorite artist?” Those questions feel shallow no matter who you are.

But for me, and for many neurodivergent artists I know, the hardest part isn’t the repetition — it’s the ambiguity.

Questions that assume mood, inspiration, or hidden meaning can feel like guesswork. They leave me searching for an answer I don’t have. Specific, grounded questions feel safer, and they help me open up.

For neurotypical artists, abstraction often feels more tolerable. They may not love those same questions either, but they can improvise an answer without the same spike of anxiety.

I’m reminded of this as I prepare for my first California show. I’m taking my parents with me. This will be their first opportunity to see my work in a show. They don’t go to galleries or art show openings, and honestly, the thought of walking into that space may be nerve-racking for them. So, I just told my Mom the plan. I will say more in the ride over, as well as when we are in the show. They won’t know the “rules,” they won’t know how to act.

But maybe that’s the point. I can explain to them what I’ve been explaining here: that I, too, feel uncomfortable in those spaces. That I don’t have a script. That I need someone at my side.

This is also one of the reasons I’ve appreciated recent conversations with Priya. She seems to understand how much steadiness matters. She doesn’t ask the usual questions; she does her homework.

And even though she’s not a professional artist, she’s actively engaged in her own practice — taking watercolor classes and working with clay because the process itself matters to her.

She knows what it feels like to wrestle with form, to create something imperfect but alive. And maybe because of that, she asks different kinds of questions.

A Better Way to Ask

So if vague or abstract questions don’t work well, what does?

For me, the best conversations begin with specific observations. They don’t have to be complicated or technical. Something as simple as:

- “This is a very interesting piece — how does it fit within your overall body of work?”

- “I noticed the repetition of this pattern — what made you return to it?”

- “This piece feels different from the others in the series — can you tell me why?”

Questions like these do two things at once: they show that you’ve really looked, and they open the door to dialogue. They don’t assume a hidden meaning or a single source of inspiration; they invite me to share how I see the piece, right now, in this moment.

And here’s the personal part: when someone asks me something specific like this, it makes the anxiety of being at a show feel a little lighter. It tells me that the person in front of me isn’t just filling silence — they’re trying to connect. That matters more than people realize.

I’m not asking anyone to come armed with the “perfect” question. I know most people walk into galleries with their own anxieties, unsure of how to act or what to say. All I’m suggesting is that if you want to connect with an artist — with me — start with what’s in front of you. Look closely, notice something, and ask about it.

That’s the difference between being a “sage on the stage” and a “guide on the side.” One dumps knowledge from a distance, expecting others to absorb it passively.

The other meets people where they are, encouraging them to discover meaning through attention and dialogue.

When someone asks me a thoughtful, specific question, it feels like they’re choosing for me to be that guide on the side — not performing, not posturing, just really looking and inviting me to respond.

And for me, that’s where connection happens.

When someone asks me a thoughtful, specific question, it feels like they’re choosing to be a guide on the side — not performing, not posturing, just really looking and inviting me to respond.

Closing Reflection

This is why my recent conversations with Priya have meant so much. Before she ever reached out to me, she had already looked over my website and studied my work. She did her homework.

She’s also deeply engaged in her own creative practice. She takes watercolor classes and works with figurative clay — not because she wants to exhibit or make a name for herself, but because the process itself is meaningful. She understands the immense complexity of the human form and finds it invigorating to wrestle with that challenge in clay. She knows what it feels like to struggle, to experiment, to keep showing up.

And maybe that’s why she asks different questions. She’s not looking for an easy answer about inspiration — she knows the process is more layered than that. For me, that difference meant everything. It felt like she was meeting me where I was, not where some script told her to be.

And that’s really the point of this whole essay. Art doesn’t need a grand explanation or a single source of inspiration. What it needs is presence. It needs someone willing to slow down, to look, and to ask about what’s right in front of them.

This essay is part of my illustrated memoir project, Lines on the Spectrum, but it’s also a beginning point for something more. I’ll soon be writing about the connection between art and spirituality — how making art has become, for me, a practice of presence.